Key Takeaways

- Mobility is the ability to access and control range of motion, not just flexibility.

- The golf swing requires adequate mobility, but far less than most golfers assume.

- Mobility does not automatically improve technique or club head speed.

- Strength training and skill practice play a bigger role than stretching alone.

- Highly effective mobility training is easy to implement in short & frequent periods

Estimated Reading Time: 18–22 minutes

1. Introduction

Most mobility content for golfers looks the same. A catalogue of exercises promising various benefits for mobility, pain relief, and golf swing improvement. I have provided plenty of these pieces myself, and they can be useful. They give golfers something quick and practical they can start implementing. But these are surface level interventions. They don’t teach golfers anything meaningful about the interaction between mobility and the golf swing.

The goal of this article is to help you understand the mobility demands of golf in detail. What is important and useful, what is not, and what this means for getting the most out of your limited training time.

I’ll be honest. I am naturally more interested in the strength, speed, and power side of golf performance. But when it comes to the golf swing, mobility becomes an important part of the discussion, and it is an area golfers are often confused about. My hope is that this article finally simplifies everything you need to know about mobility for golf.

Traditionally, golfers have put a huge emphasis on stretching and flexibility. Nobody questions it. The same cannot be said for strength and speed training, which are often questioned or criticized in golf. If you are interested in strength & speed training, I recently released comprehensive guides.

I hope this article makes “mobility for golf” something you finally understand. Time to dig in.

2. Understanding Mobility

Before going any further, we need to define what mobility actually is. Golfers talk about mobility all the time, but we need to make sure we are talking about the same thing.

Mobility is your ability to move a joint through a range of motion with control.

In complex movements like the golf swing, joints do not work in isolation. What matters is not just how far a joint can move, but whether you can access and control that range as part of a coordinated movement.

That is the key distinction between mobility and flexibility.

Mobility is usable range. It is the range you can reach, coordinate, and control on your own.

Flexibility refers to the ability of muscles and connective tissue to lengthen. It can be expressed actively or passively, depending on context, but it does not automatically imply control.

The two qualities are related, but they are not the same thing, and they do not require the same type of training. Golfers often use the words mobility and flexibility interchangeably, which is understandable, but from a movement and performance standpoint, they describe different characteristics.

Flexibility matters. If tissue cannot lengthen enough to allow a position, that position will not be accessible actively. Flexibility, however, does not automatically show up in your golf swing. When thinking about range of motion in the golf swing, we need to consider the velocity and force of the movements we are performing.

The golf swing is fast, powerful, and highly coordinated. To use a range of motion at speed, the body needs strength and control in that range. Without that, the nervous system often limits access as a protective response.

This is why golfers can spend significant time stretching, feel looser, and still see little change in how they move when they swing.

Later in this article, we will look in detail at what actually influences mobility, including nervous system behaviour, tissue adaptation, and joint structure. We will also cover how much mobility the golf swing truly requires, how strength and power training interact with mobility, and how to train it sensibly.

Now that we have a clear definition of mobility, we can look at why it matters for the golf swing, where it plays a role, and why more is not always better.

3. How Much Mobility Do We Need?

Mobility matters in golf because the swing requires coordinated movement through specific joint angles at reasonably high speeds. Certain parts of the body do need to move well if you want a full, efficient, repeatable swing. There is no getting around that.

Professional golfers generally have better mobility than the average sedentary adult, particularly in the areas the golf swing stresses most. We will dig into these areas later in the article, where the influence of mobility on club head speed is explained. Pros make hundreds of swings per week and have often been doing so since childhood. That alone develops a baseline level of mobility and control, especially in golf-specific patterns.

Where things get misunderstood is in how much mobility is actually required for elite golf.

The ranges of motion involved in a high-quality golf swing are not extreme. They are greater than what many people display in daily life, but they are nowhere near the circus-level flexibility some online mobility content implies. Professional golfers are often mobile, but they are not contortionists. I have worked with PGA Tour players that have earned tens of millions of dollars playing golf, and have average to poor mobility. Their swings look fluid and expansive because their movement is well sequenced and coordinated, not because their joints move through unusually large angles.

If usable range is insufficient in key areas, the swing becomes harder. Golfers compensate, lose structure, or run out of room. In those cases, mobility genuinely matters.

Just as important, however, is what mobility does not do.

Mobility does not guarantee good technique.

Mobility does not improve clubface control.

Mobility does not automatically increase speed.

You can be very mobile and still swing poorly.

You can be only moderately mobile and swing extremely well.

Most golfers drastically overestimate how much mobility is required for a great swing. They assume professionals rotate far more than they do. They assume swing faults are caused by “tightness,” when the real issues are usually concept and lack of practice time based. I went into a bit more detail on that in this article about mobility in the golf swing. There is absolutely no shortcut to high level golf. It requires a large volume of practice, likely over many years.

Once you have the mobility required for the swing movements you want, plus a small buffer so you are not living at end range, more mobility adds very little. From that point on, improvements come from skill, strength, and sequencing, not from stretching deeper.

So yes, the golf swing requires mobility and elite players generally have more of it than amateurs. But the ranges required are moderate, and most amateurs already have enough mobility to swing far better than they do. What they lack is the ability to use that range effectively. Fixing this comes down to technical development.

Next, we’ll look at what actually limits mobility.

4. What Actually Limits Mobility

When golfers think about mobility, they usually assume the problem is simple: “my muscles are tight.” That can be part of the picture, but it is rarely the main reason someone is restricted in a movement.

Mobility is influenced by three primary factors:

- the nervous system

- muscle and connective tissue

- joint structure and anatomy

Understanding these factors makes mobility training far more effective. It also prevents golfers from chasing the wrong solutions and, in some cases, irritating joints that were never meant to move further in the first place.

The most common limitation is not tissue length. It is the nervous system.

Your brain ultimately decides how far you are allowed to move. If a position feels unfamiliar or potentially risky, the nervous system limits access to that range as a protective response. It is essentially saying, “that is far enough for now.”

This is why range of motion can improve very quickly during a warm up. Your tissues are not changing meaningfully in a few minutes. What is changing is your nervous system’s willingness to allow movement into those positions (plus warmer tissue).

You can demonstrate this easily. If you stand up and perform several slow, deep squats, you will often notice that each repetition feels easier and allows slightly more depth. Your muscles have not lengthened in those few seconds. Your brain has simply registered that the movement is safe.

Most golfers have not shown their nervous system that they can control the ranges they already possess. Gradually moving through deeper ranges, and doing so regularly, allows the nervous system to relax its protective response and makes existing range easier to access.

Muscle and connective tissue do matter, but they are often over emphasised.

Tissue adapts to what it is exposed to. If certain ranges of motion are rarely used, especially rotational end ranges, the muscles and connective tissue involved become comfortable operating at shorter lengths and less tolerant at longer ones. This is not damage or dysfunction. It is a normal adaptation.

Most golfers spend decades in a small number of postures. Sitting dominates daily life. Rotation is limited. Joints are rarely challenged near the ends of their available range. Then, on the golf course, the body is asked to rotate quickly and forcefully through much larger ranges.

Over time, tissues adapt to this lack of exposure in predictable ways:

- collagen fibers stiffen around the postures used most often

- muscles function well in mid range but feel weak and uncoordinated at longer lengths

- tissue hydration changes, contributing to the sensation of stiffness

- connective tissue layers slide and glide less freely

- rotational end ranges feel foreign simply because they are rarely visited

There is nothing “wrong” with this tissue. It is simply not accustomed to lengthening, particularly at speed. When you suddenly ask it to do so, the nervous system limits range to protect you.

This is not aging. It is not being inherently inflexible. It is a lack of exposure.

The positive side is that tissue also adapts when you train into end range consistently and with control. These changes happen slowly, but they are achievable.

When joints are gradually taken toward their end ranges under control, tissues:

- become more tolerant to stretch and tension

- remodel to handle load at longer lengths

- develop strength in positions that previously felt weak

- reduce the nervous system’s protective response

- improve sliding, gliding, and hydration characteristics

The muscle is not dramatically “lengthening.” It is becoming more capable and comfortable at longer lengths because it has been trained there.

This is why long range strength training and active mobility work are effective. They improve mobility not by pulling tissue longer, but by increasing strength and tolerance in the positions you want to use.

Some mobility limits, however, have nothing to do with training at all.

Joint structure places real constraints on how much motion is available. Bone shape, socket depth, and joint orientation determine how far certain joints can move. Hip rotation is the clearest example. Some golfers naturally have large rotational capacity. Others reach a firm stop much earlier. The same is true for the shoulder. In these cases, trying to force more range will likely do more harm than good. You are trying to change something with a small adaptive capacity, and could end up with more aggravation than progress.

Signs of a structural limitation include:

- a hard, unmistakable end range block

- deep joint pinching rather than a muscular stretch

- no improvement with warming up

- passive range equaling active range

Structural variation is normal and does not determine golfing potential. Some golfers have a lot of hip rotation. Some have less. Excellent golf can be played with either profile. The key is recognising what is modifiable and what is not worth chasing.

Once you understand these three limitations, mobility training becomes straightforward.

If the nervous system is the main limiter, improvements can happen quickly.

If tissue tolerance and control are the issue, progress is gradual and requires consistency.

If anatomy is the limiter, it is not changing, and that is fine.

This framework prevents golfers from stretching things that do not need stretching, chasing ranges their joints do not have, blaming tightness for technique problems, and wasting large amounts of training time.

It also explains why golfers feel dramatically different once they are warmed up. Nothing structural changed. The nervous system simply allowed more access to existing range.

5. Mobility Training Myths and Realities

One of the most common fears golfers have about lifting weights is that it will reduce mobility. Many worry that strength training shortens muscles, restricts the swing, or costs them range of motion. This belief is widespread in golf, and it is wrong.

Strength training improves mobility, and when performed through appropriate ranges of motion, it does so to a similar extent as stretching. Large systematic reviews and meta-analyses comparing resistance training and stretching show that strength training does not reduce joint range of motion and consistently leads to meaningful improvements when full ranges are used (Afonso et al., Sports Medicine).

The myth comes from how many people actually train. If lifting is only performed through partial ranges of motion with no exposure to end-range positions (aka big stretches), it won’t be effective for improving or maintaining mobility.

From a muscle physiology standpoint, force production varies across the length of a muscle. Muscles are naturally weaker at longer lengths. If those positions are never trained, force capacity remains low and the nervous system treats those ranges as unstable or risky. Training through larger ranges increases force capacity at longer muscle lengths, making movement through those positions feel easier and less guarded.

For golfers, this matters because the swing repeatedly places muscles and connective tissue into lengthened positions under significant load. Strength training prepares tissue for that demand in a way passive stretching does not.

Over time, loading tissue at longer lengths also leads to structural adaptation. Muscle architecture can change by increasing fascicle length, while connective tissue adapts through collagen remodeling that improves tolerance to tensile strain near end range (Freitas et al., Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports).

Stretching still has a role, but it needs to be framed correctly. Stretching can increase range of motion and improve comfort in a position, but it does little to improve strength or control within that range. In fast, forceful movements like the golf swing, any range that cannot be controlled under load is unlikely to show up reliably.

Stretching is also commonly overvalued for injury prevention and recovery. Large reviews show that static stretching does not meaningfully reduce overall injury risk or delayed onset muscle soreness when used on its own (Behm et al., Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism; Herbert & Gabriel, BMJ).

For preparation and recovery, light movement and dynamic activity are generally more effective than prolonged static stretching. Stretching can help golfers feel looser or calmer, but it should not be relied on as a primary strategy for long-term mobility development, injury prevention, or recovery.

When framed appropriately, stretching becomes a useful supporting tool rather than a misplaced solution.

6. Mobility and Club Head Speed

Club head speed is primarily determined by;

a) The length of the hand path in the downswing

x

b) The average force applied along this hand path

Time applied (a) x average force (b) = the amount of impulse applied to the club.

The higher the impulse, the greater the change in momentum of the clubhead, which we measure as club head speed at impact.

Consider hand path length as a runway. With a longer runway, we have more time to accelerate. This is why hip, thoracic, and shoulder mobility are important. They provide us with the physical requirements for a longer hand path.

Another analogy we can learn from is wedge play. By changing how far we move our hands in the backswing when chipping or pitching we can drastically alter the club head speed at impact, without trying to apply more force. This is due to having more time to apply force during the downswing. We can use this same concept when trying to increase club head speed in the full swing. Usually get your hands to 10 o’ clock? Get them to 10:30 or 11 o’ clock and your club head speed will likely increase.

The average force applied will be dictated by your kinematic sequencing, the explosive capabilities of your nervous system and muscles, and your level of effort. Your mobility will be important for kinematic sequencing as this is what allows us to create some separation or stretches between different segments of the body. These quick stretches, which happen in a large number of segments in the body during the swing, are important for club head speed, and quality of swing in general.

The information above is describing linear work in the golf swing. There is also relevance to how much angular work is done. This refers to how far the shaft has rotated “around the clock”.

Here is a passage from Sasho Mackenzie’s paper “How Amateur Golfers Apply Energy to the club” that sums up these concepts…

It was determined that linear work predicted 90% of the variability in clubhead speed, while angular work only predicted an additional 9%, and gravity had no predictive ability.

The average force applied in the direction of travel of the hand path was by far the biggest discriminator in separating individuals with different levels of clubhead speed, as it predicted 92% of the variability. From a practical standpoint, knowing that a higher level of average force most likely explains differences in clubhead speed does not suggest a clear path for an instructor, or golfer, trying to increase clubhead speed. The reason is that a higher average force could be the result of several diverse factors such as swing coordination, level of exertion, and the force generating capabilities of the primary muscles involved.

This summary is further evidence that more mobility is likely not going to be a huge player in club head speed, as average force applied to the club, not hand path length, is by far the biggest discriminator in club head speed. Average force has less to do with mobility, and more to do with swing technique and muscle strength.

So yes, we need adequate mobility, but more is not necessarily better.

7. Mobility-Based vs Skill Based Limitations

One of the most common mistakes golfers make is assuming that improving mobility will automatically fix a “swing fault”.

A golfer struggles to turn, has a short swing, early extends, or any other example, and the conclusion is often simple: “I’m just not very flexible”.

Sometimes that is true. Most of the time, it is not. In almost all of these cases, with guidance from a good coach, the golfer can make the desired movement pattern once they are given the correct information and guidance.

In many cases, what looks like a mobility problem is actually a concept and awareness problem. The golfer does not lack the physical ability to move into the desired position. They lack an understanding of how to move there, and more importantly, they have yet to develop a motor pattern that allows them to do it reliably in a real swing – with a golf ball and consequences.

Mobility gives you capacity to perform a movement but you need to know what to do with it in the swing. It’s entirely possible for someone with great mobility to have a short swing with little turn. On the contrary, I guarantee you there are excellent senior golfers, with average mobility at best, that have beautiful free flowing looking swings.

Your golf swing is a deeply ingrained motor pattern built through thousands, and often millions, of repetitions, and reaction to the consequences of those repetitions over many years. Once that pattern exists, the nervous system strongly prefers to keep using it.

If mobility improves but the motor pattern does not change, and it won’t without specific training of the actual skill of hitting golf shots, the body will most likely use the swing pattern it has always used. More available range does not mean the brain will change the pattern.

This is why golfers can stretch, feel looser, and then swing exactly the same way they did before.

There are situations where mobility genuinely limits the swing. I am not trying to dismiss the merits of working on mobility. I do so for a few minutes daily. If a golfer physically cannot reach a position even when moving slowly, with focus, and without the pressure of hitting a shot, then mobility may be a real constraint.

A simple way to check if a mobility limitation is the main cause for your swing issue is to remove speed and outcome from the equation. Ask yourself:

- Can I perform the movement with a slow motion swing?

- Can I do it without a ball present?

- Can I do it while hitting a ball into a net, where the result does not matter?

If the answer is yes, mobility is not the main issue. You have just proven to yourself you have the range of motion. Coordination and trust get harder as speed of movement, and desire to hit a functional shot go up. These are technique development or movement learning issues, and they are completely normal.

If the answer is no, and you feel a genuine restriction rather than lack of coordination or simply an “alien” feeling from a new movement, then mobility work is necessary. If the desired movements are right on the limit of your current range of movement, it’s not ideal. We want a bit of a buffer.

Check out this 5 exercise golf mobility routine.

The presence of a golf ball and target changes how you move. Once a target exists and you are trying to hit a functional shot, the nervous system prioritises “survival”, which in this case is an “OK shot outcome” rather than technical change. It defaults to whatever pattern it knows best and is least worried about committing to.

This is why golfers can often perform movements well in drills, rehearsals, or slow swings, and then immediately revert to old habits once speed and outcome return.

Getting specific with mobility training:

Swing drills or rehearsals can be great mobility training. When we perform a swing exaggerating the movement we are trying to implement with focus and control, and slightly larger ranges, our mobility is being trained in the exact movement pattern that needs to change….albeit at a slower speed and without the consequence of hitting a shot.

This has two advantages. Mobility improves in a way that transfers directly to the swing, and the new motor pattern is trained at the same time. We are giving our brain a chance to get accustomed to the new movement. This is far more effective than improving mobility in isolation and hoping it appears later.

That said, some restrictions are easier to address with targeted mobility work. This is why isolated mobility exercises still have value and why there are “swing specific” mobility routines in the Fit For Golf App. The key point is that mobility training does not need to be separate from swing training.

Finally, structural limits still apply. If a limitation is structural and presents as a hard block that does not improve with warming up, slow movement, or targeted mobility work, it is unlikely to change. In these cases, the solution is not more mobility training, but learning to work within what your structure allows. Trying to force movement where anatomy does not permit it is rarely productive and often leads to irritation.

To summarise, before assuming a swing fault is caused by poor mobility, ask a simpler question:

“Can I perform the movement slowly, without pressure, if I know what I am trying to do?”

If yes, the issue is skill and coordination.

If no, mobility is part of the solution.

Understanding this distinction saves golfers enormous time and frustration. It also prevents mobility training from becoming a distraction from the real work, which is learning how to swing the club better.

8. Assessing Mobility for Golf

This article is primarily theoretical, but I did want to provide you with a very quick mobility assessment you can perform on yourself. All of these tests are taken from the TPI Level 1 assessment, and target key areas.

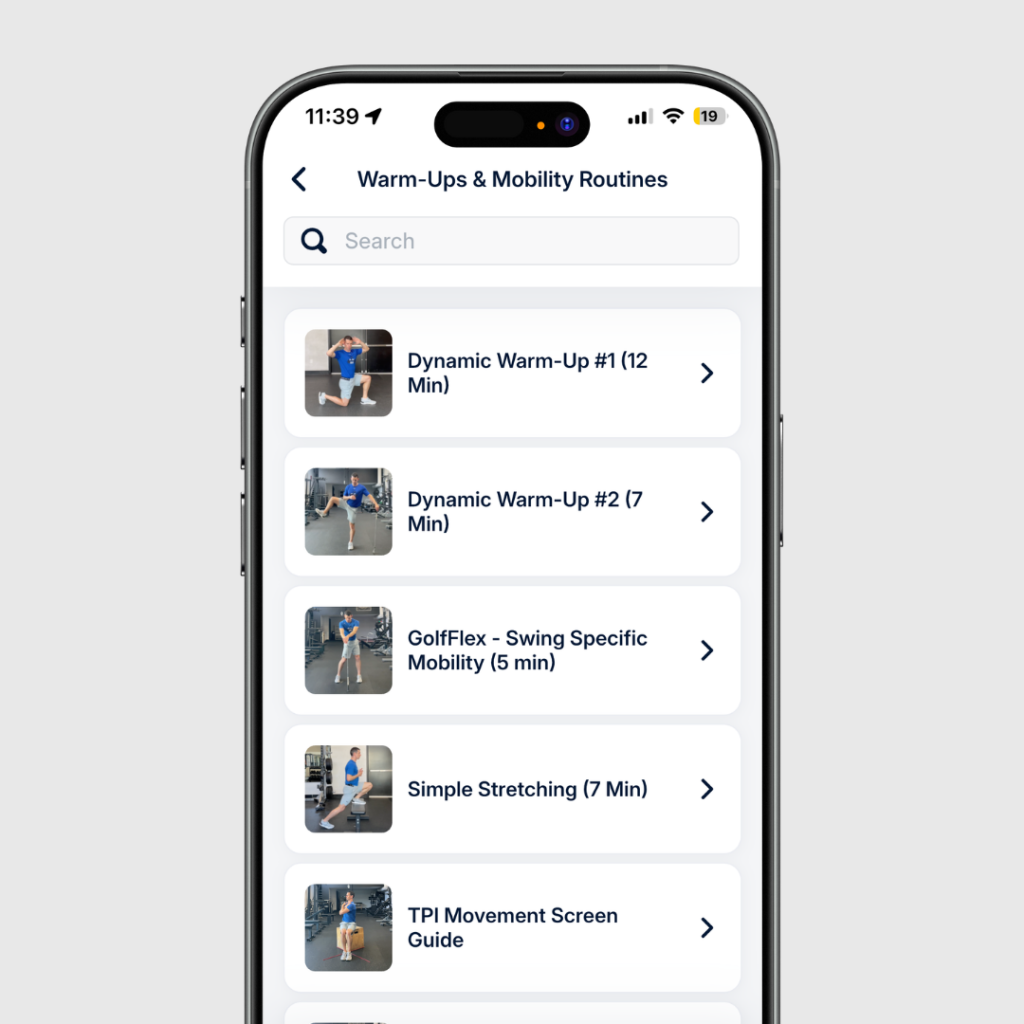

If you are interested in seeing the full TPI Level 1 Screening, and my interpretation of the value of the different exercises included, check out the “TPI Screen – Self Assessment Guide” in the Fit For Golf App. It’s in the “Golf Warm-Ups & Mobility Routine Section”

It’s common to assign “pass” or “fail” gradings to exercises in screenings. I am not a fan of this, as it misses out on key context. For example, in test #1, Lower Quarter Rotation, the shaft on the ground represents a 60 degree angle. This range of motion is quite difficult, especially for the internal rotation test. Most people fail. However, someone “failing” at 55 degrees, versus 30 degrees is obviously quite different. There is a 25 degree difference in range of motion, versus a 5 degree difference between 55 and 60 degrees, which is pass. In this example, the golfers with 30 and 55 degrees are lumped in the same category as “limited internal hip rotation”, yet the golfer with 55 degrees is much closer to the 60 degree “pass mark” than they are the other golfer that “failed” with 25 degrees.

My point is to use these as gauges for where you currently are, and see if you can improve. This is much more beneficial than thinking you can’t do X in your swing because you “failed” Y test.

Lower Quarter Rotation

Seated Thoracic Rotation

External Shoulder Rotation

Shoulder Flexion

Interpreting What You See

How these exercises feel and respond to repetition and target work is important.

If a movement improves noticeably with warming up or repetition, the nervous system is likely the main limiter. In these cases, regular exposure, slow rehearsal, and controlled movement through the range are often sufficient.

If a movement presents as a hard block that does not change with warming up or repeated attempts, or is painful, it is likely structural. In these cases, the goal is not to force more range, but to work within what your structure allows and organise the swing accordingly.

Understanding which category you fall into prevents you from wasting time and effort that could be spent on more trainable things.

9. How to Implement Mobility Training

Let’s first remember that mobility is improved with well programmed strength training, and can be worked on in your golf drills. So even without separate mobility work, you can improve it.

With that being said, I do think mobility should be worked on separately in a more targeted fashion.

Like any other physical quality, it is getting worse with age, unless we actively fight against it.

There are two main ways I suggest implementing mobility work, and the good news is that they don’t take long.

1) Good quality dynamic warm-ups – If you are reading this, you likely exercise and practice frequently. You can simply add a dynamic warm-up routine to the beginning of these activities. This will of course serve as great preparation for your upcoming session, but also stack up to very valuable long term mobility gain and maintenance.

Workout 3 x week and play golf or practice 3 x week? Five minutes of dynamic mobility work beforehand will be hugely beneficial, and it adds very little time or effort to your already well established routines.

Dynamic Warm-Up #1 and #2 in the Fit For Golf App are perfect for this. I do Dynamic Warm-Up #1 pretty much every day, either before practice, play, or workouts.

2) Part of a daily maintenance plan – Mobility is not different to strength training or cardio in that it’s not fatiguing. We can do it from anywhere simply as part of our day.

We don’t require any equipment or workout clothes, we don’t need to shower afterwards before going back to work, or even leave our workspace. You can quite literally just insert a simple 5 to 10 minute, or even 2 minute routine into your day.

If you use the Fit For Golf App for your workouts, you are likely working out three times per week on non consecutive days, and doing Dynamic Warm-Up #1 before these workouts.

A nice contrast would be to try GolfFlex or Simple Stretching on the days in between workouts. Both of these routines are less than 10 minutes and can be done anywhere. It’s that simple, no warm-up or special prep required.

Pretty easy, right? The key is making it a habit. The app really helps with this. Start your daily routine and reap the rewards on and off the course.

Fit For Golf App Success Stories

61-year-old, 2 hcp golfer Eric used the FFG App for 6 months:

- Swing speed up from 97 → 109 mph

- Better hip, ankle & torso mobility

- Friends noticing his improved turn

“It’s been a game changer for my distance and movement.”

Since using the Fit For Golf app, Brian has:

- Gained 12mph club head speed

- Lost 10lbs

- Dropped his handicap by 5

- Crushed drives 300+ yards!

References

Strength Training versus Stretching for Improving Range of Motion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(4):427. doi:10.3390/healthcare9040427

Freitas SR, Mendes B, Le Sant G, Andrade R, Nordez A, et al.

Can chronic stretching change the muscle-tendon mechanical properties? A review.

Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2018;28(3):794–806.

Behm DG, Blazevich AJ, Kay AD, McHugh MP.

Acute effects of muscle stretching on physical performance, range of motion, and injury incidence.

Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 2016;41(1):1–11.

Herbert RD, Gabriel M.

Effects of stretching before and after exercising on muscle soreness and injury risk.

BMJ. 2002;325:468.

Mackenzie SJ, Sprigings EJ.

How amateur golfers apply energy to the club.

International Journal of Golf Science. 2020.