Table of Contents

- Why Strength Is Important for Golfers

- How Do We Get Stronger?

- Applying This Knowledge to Training

- What Muscles Do We Want to Stimulate Adaptations In?

- Training Structure and Planning

- Strength Training vs Resistance Exercise

- How Heavy Should I Lift?

- Safety, Myths, & Flexibility

- Practical Application: Periodised Training for Golfers (Fit For Golf Programs)

- The Big Picture

1. Why Strength Is Important for Golfers

Strength is important for golfers because it plays a huge role in how much club head speed we can produce. Muscles are what create force, and the stronger our muscles are, the more potential we have to generate club head speed. This is critical for golf because club head speed plays such a big part in our golf potential. At every level of the game you go up, average club head speed increases. Club head speed doesn’t guarantee anything, but there are certain thresholds you must be at to make your particular golf goals realistic.

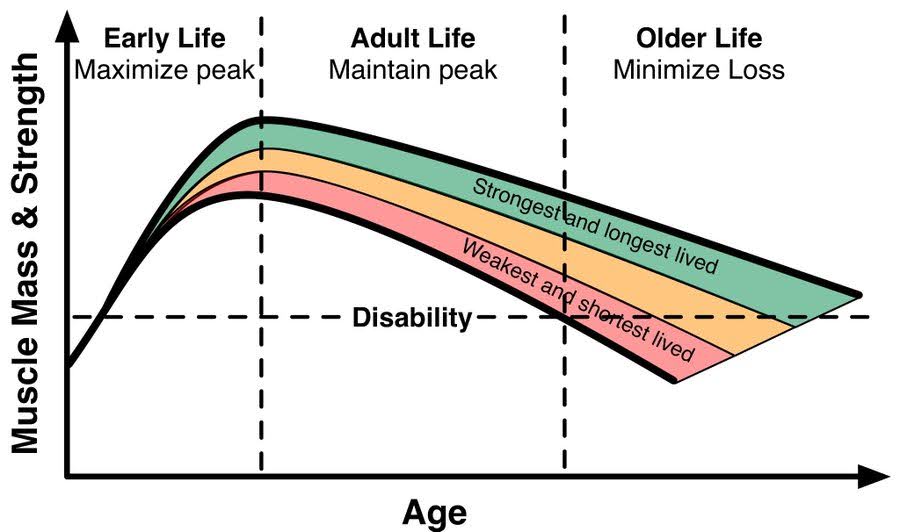

Strength matters in the short term for performance, but also long term, for golf longevity. One of the main reasons golf performance declines with age is the steady loss of distance that happens as we lose muscle mass, strength, and power. While many aspects of skill may stay sharp, or even improve, the decline in physical capability changes the type of golf we can play, how our body feels during and after a round, and potentially how much we enjoy it.

70 year olds stronger than 25 year olds? A research review, highly applicable to golfers.

Most of us play golf for recreation, but if you’re reading this, you probably get satisfaction from improving and maintaining a certain standard of play. It’s frustrating when your ability starts to decline, especially when the main cause is extremely dependent on our commitment to physical training.

High quality, structured, strength training is by far the best antidote we have for the aging processes that reduce club head speed and golf performance. It also lowers injury risk, allowing you to practice and play more often with a body more conditioned to handle the demands of the game. Nobody likes needing to take time out from golf due to injuries.

So, whether your goal is to maximize club head speed and lower your handicap, regain distance you’ve lost, or simply stay healthy enough to keep playing the game you love, strength training needs to be part of your routine.

Of all the areas of golf performance I write about, this is the one I have the deepest passion for and experience in. By the end of this article, you’ll understand exactly why and how golfers should strength train, and how to apply it to see both short and long term progress.

2. How Do We Get Stronger?

Strength training works by stimulating adaptations in the neuromuscular system. The neuromuscular system is made up of the nervous system and the muscular system.

These neuromuscular adaptations can be grouped into two main types:

Neural adaptations – how the nervous system sends signals to the muscles.

Structural adaptations – physical changes in the muscles and connective tissues.

| Adaptation Type | Specific Adaptation | Explanation | Transfer to Club Head Speed |

| Neural | Increased Fast Twitch Motor Unit Recruitment | Learning to activate a higher percentage of fast twitch muscle fibers. | High – recruiting more fast twitch fibers means more potential for speed. |

| Neural | Rate coding (firing frequency) | The nervous system increases the speed and coordination of signals sent to muscle fibers. Needs explosive intent in reps for maximum benefit. | High – faster firing improves how quickly force can be produced. |

| Neural | Intermuscular coordination | Different muscles involved in a movement work together more efficiently and in the correct sequence. | Low – largely limited to the trained movement pattern and velocity. |

| Structural | Type IIa (fast twitch) fiber hypertrophy | Increases in the size of the fast twitch fibers responsible for high force and velocity. | High – bigger fast twitch fibers produce more force and power. |

| Structural | Tendon stiffness | Stronger tendons can store and release elastic energy more effectively. | Low – the golf swing is more muscle-driven than tendon-driven. |

| Structural | Fiber type shift (IIx ↔ IIa) | Strength training tends to convert our fastest twitch fibers IIx to slightly slower IIa fibers. | Moderate – training style matters; larger IIa size may offset IIx loss. |

Neural adaptations from strength training improve the signals we send from the brain to our muscles. This is an untapped source of strength potential that can be improved rapidly, and can lead to improvements in strength, power, and speed, without any changes in the actual muscle tissue.

Structural adaptations from strength training lead to changes in muscle and connective tissue that allow us to increase force production. A classic and relevant example is an increase in the size, our cross sectional area of the fast twitch (type IIa), muscle fibers.

While this article focuses on strength training, I must mention that higher speed training, both in terms of workouts, including, sprints jumps, medicine-ball throws, slams, other explosive lifts and most importantly specific swing speed training, play an enormous role in stimulating these neural and structural adaptations for increasing club head speed.

In the Science of Speed Series I wrote about adaptations that occur as a result of high-speed training.

In my understanding and opinion, there are two key adaptations golfers benefit from most as a result of strength training: Increased Motor Unit Recruitment and increased size of the fast twitch muscle fibers. Improvements in each of these make perfect sense for increasing our ability to generate club head speed.

All progress follows the same process:

Stimulation → Adaptation → Enhanced Capabilities.

The reason I laid out the various adaptations is that I want you to take an “adaptation focused” approach to strength training, rather than an “exercise focused” approach.

Once you understand that it is these adaptations that improve our ability to generate club head speed, the question is no longer “What exercises are best?”, but instead, “What adaptations am I trying to stimulate?” The exercises we choose are important, but completely irrelevant if they do not stimulate adaptation.

As long as the stimulus keeps progressing, the body keeps adapting. When it stops, progress stops too. Unfortunately, many people strength train in a way that leads to little or no adaptation.

3. Applying This Knowledge to Training

Heavy vs Moderate vs Light Loads

1RM refers to one-rep max — the most weight that can be successfully lifted for one rep in a particular exercise. This amount is commonly used as a baseline to assign training weights.

You do not need to, and shouldn’t, test your 1RM in each exercise. There are simple formulas based on training weights that will give you a good estimate, and the Fit For Golf App calculates it for you.

Not all loads create the same adaptations. Heavy (85 % + of 1RM), moderate (65–85 % of 1RM), and light (< 65 % of 1RM) training can all make positive progress, but the adaptations are not equal. Adding more reps with light weights, while capable of increasing muscle mass just as well as heavier strength training, will not be as effective for increasing strength and power. There are neural and structural reasons for this.

When comparing heavy, moderate, and light loads for their effect on muscle growth, it’s critical that proximity to failure is standardized, otherwise the sets could be of vastly different effort levels. A set of 5, 12, and 20 reps taken to roughly 1 rep in reserve (i.e. one more rep but no more would have been possible at the end of the set) will create a very similar hypertrophy stimulus for type IIa fibers. The key difference is that heavier loads emphasize neural adaptations much more strongly, which are especially valuable for golfers aiming to increase strength and power.

Lighter loads can match hypertrophy when effort is equal, but they don’t produce the same neural benefits and come with higher fatigue.

It also leads to greater post-workout fatigue that takes longer to recover from and shifts fibers toward a more endurance or slow-twitch profile. This is not ideal for explosive power, though it can support the goal of increasing type IIa fiber size.

Heavy loads: Using a weight that can be lifted for five reps or fewer per set is best for building maximum strength. They are especially effective for improving our ability to recruit high-threshold or fast-twitch muscle fibers. Moderate and especially light loads are not as good for stimulating this adaptation. When weights are near our maximum, we are forced to recruit all of our muscle fibers to move the load. There is no option but to “turn everything on.”

Muscle fibers are recruited on a force basis. For low-force, low-intent activities, there is no need to recruit fast-twitch fibers, so they aren’t trained. As the intent or necessity to produce more force increases, more fast-twitch fibers are recruited and trained. The harder we tell our brain and muscles to push, the more fast-twitch fibers we recruit, even if the load is moving slowly because it’s heavy relative to our strength level.

When we begin strength training, we’re incapable of recruiting all of our fast-twitch fibers because we’ve never needed them before (unless you’ve come from explosive sports). As we continue practicing heavy lifts relative to our strength level, we get better at recruiting these fibers. This ability directly transfers to swinging a golf club. The adaptation is best stimulated by strength training, but it carries over when we swing.

For example, most golfers know leg strength matters for club head speed. We can enhance leg strength much better through strength training than with golf swings alone, and this enhanced strength shows up when we swing. The adaptations in our nervous system and muscles are transferable.

Heavy loads are also very effective for increasing the size of type IIa fibers. The only issue from a practical standpoint is that to maximise hypertrophy, you need a fairly high training volume, and that gets difficult when using weights so heavy you can only perform 1–3 reps per set. This is why periodising training is valuable.

I tend to program heavy loads for primary exercises, in big compound movements, like squats, split squats, deadlifts, RDL’s, bench presses, overhead presses, pull-ups and rows.

Moderate loads: Which allow approximately 6-12 reps in a set, are extremely effective for increasing the size of type II fibers, and will improve neural adaptations. Just not as much as heavier loads. There is definitely a place for these in a golfers training program, and they feature regularly in the Fit For Golf App for assistance exercises.

When the primary goal of a training period is increasing the size of the fast twitch fibers, a key structural adaptation for golfers, especially in the off season, a focus on moderate loads is a very logical option. This is why they feature so prominently in the Mass Program.

Light loads: Which is using a weight that allows approximately 12-20 reps per set, are equally as effective as heavy & moderate loads for increasing size of the type IIa fiber. They are not as effective for stimulating neural adaptations beneficial to golfers.

The limiting factor in light load training is also different to that of heavy training. In heavy training, the ability to produce enough force to move the load is limited purely by your force production capability. Due to the set duration being quite short, there is very little metabolic fatigue built up. This is completely different in light load training. There is a huge amount of metabolic fatigue built up, and the ability to deal with this metabolic byproduct becomes a big element of how many reps are completed. This “feeling the burn” at the end of high rep sets, which we actually don’t really want much of, when the goal is maximising strength and power adaptations.

These types of sets, when taking close to failure, also take longer to recover from than heavier training, which isn’t good for speed training or golf practice. This is why you don’t see high rep sets of 12+ in the Fit For Golf App. It’s not that they are bad for us, they are a perfectly OK training choice if your goal is general health or increases in muscular size and endurance, they just aren’t as effective for improving golf performance.

Takeaways

For golfers, the sensible zone most of the time is around 3-8 per set, depending on the type of exercise, leaving one or two reps in reserve. This range provides enough load to stimulate neural and structural changes without creating excessive fatigue.

From a percentage of one rep max perspective, this tends to fall around 75–85% of 1RM, but it varies a lot between exercises and between people. That is why percentages are a guide at best. The relationship between load and effort changes based on the lift, the person, and the day. This is why I prefer using effort based targets. If you finish a set knowing you could have done 1-3 more good reps, you are training in the right zone.

Going all the way to failure on each set creates more fatigue than is necessary, and can detract from total volume and quality of a training session, and if there are too many reps in reserve at the end of a set, you won’t stimulate adaptation.

In general, most beginner and novice trainees are bad at estimating how many reps they had in reserve at the end of a set. They usually think they were much closer to failure than they actually were, which results in not training hard enough. For this reason, it is good to sometimes test exactly how many reps you can perform with a given weight, going all the way to failure.

You need to be smart with this, choosing sensible exercises, and using a spotter and safety mechanisms. Please don’t get stuck under a bench press or at the bottom of a squat!

4. What Muscles Do We Want to Stimulate Adaptations In?

Time is limited, so we need to target the movement patterns and muscle groups that give the biggest return for the effort we put in.

The golf swing relies on strength through the entire body, but especially in the muscles used earlier in the motion. These are the muscles that get the body moving from a static position and generate the torque and angular momentum that are transferred up the kinematic chain and ultimately to the club.

In an efficient swing, the body follows a “proximal-to-distal” sequence. Power starts in the muscles closest to the body’s center and moves outward. The legs and hips initiate the motion by exerting force against the ground. The ground then pushes back with equal force, allowing that energy to travel up through the trunk, into the shoulders, arms, and finally the club. Each segment builds on the momentum created by the one before it, reaching a higher peak velocity.

Because the lower body and trunk are moving more slowly at the start of the swing, they rely heavily on strength to generate motion. The limbs later in the chain are moving much faster and depend more on timing, coordination, and speed.

So in terms of where strength training gives the biggest payoff for golfers:

- Legs and hips — the initial source of force in the chain. More strength here creates a larger potential for club head speed.

- Trunk and core — actively produce and transfer force between the lower and upper body.

- Upper body and arms — benefit from the momentum generated by the segments earlier in the sequence, but still play an important active role in delivering speed to the club.

Upper-body strength still matters, but by the time those muscles fire, the club is already moving quickly. That’s why strength work builds the foundation, and specific speed training teaches you to use that strength at the higher velocities seen in the swing.

The majority of a golfer’s strength training should focus on compound lifts that train large amounts of muscle mass and multiple joints together. Squats, split squats, deadlifts, presses, and rows are the foundation. These provide the most room for long term progression, and the biggest neural and structural changes that improve force production.

Accessory exercises, including isolation exercises, still have a place, but they should be supporting the main work, not replacing it. Use them to build up smaller areas, work on weak links, or keep joints healthy.

For example, increasing your hamstring curl or quad extension strength by 30% is not going to have the same transfer to club head speed as increasing your barbell squat by 30%.

This doesn’t mean it’s not beneficial though!

| Region | Role in the Swing | Key Muscles | Best Lifts / Movements | Notes |

| Legs & Hips | Create and transfer force from the ground. Initiate angular momentum | Glutes, quads, hamstrings, adductors, calves. | Squat, split squat, deadlift, trap-bar deadlift, hip thrust, leg press, hack squat. | Strong legs and hips provide the base for generating and transferring force, not the sole driver of club head speed, but a key foundation. |

| Trunk & Core | Generate force, and transfer force from the lower body to the upper body. | Abdominals, obliques, erector spinae, QL. | Cable rotations, back extensions, side bends, ab wheel roll outs, hanging leg raises. Also well trained in big compound exercises |

The core actively produces and transfers force, train it like other areas, following progressive overload! |

| Upper Body (Push) | Helps speed up the arms.

|

Pecs, shoulders, triceps. | Bench press, overhead press, landmine press. All presses. |

Remember, we are training adaptations. It doesn’t matter that these exercises seem “not golf specific”. |

| Upper Body (Pull) | Produce and control rotational torque, especially lead-side. | Lats, rear delts, rhomboids, traps, biceps. | Pull-ups & chin ups, lat pull downs, rows. | Lead side lat and shoulder play a huge role in club head speed. |

| Forearms & Grip | Assist in force production & transfer force to the club. | Forearm flexors/extensors, hand muscles. | I don’t train grip specifically. I think it gets covered extremely well from heavy lifts and speed training. | It’s hard to not develop a strong grip if you are pushing and pulling progressively heavier weights. Grip strength is generally NOT a limiting factor in club head speed. |

5. Training Structure and Planning

Full-Body Training Splits

I program strength training as full-body splits two or three times per week for almost all golfers. It keeps scheduling simple and allows more time for the other things that matter — golf practice and play, speed training, cardiovascular training, and life outside the gym.

Each full-body workout includes some lower-body, core, and upper-body work. The exercises in each workout are adjusted so that across the week, all key movement patterns and muscle groups are trained sufficiently. This is very different from the traditional bodybuilding approach of “arms day,” “back day,” or “legs day.” Those routines were designed for physique goals, not for improving strength, power, and performance in a sport like golf.

Full-body sessions are also less fatiguing for each muscle group. You give every area a small dose of work, recover quickly, and repeat. This approach works much better than hammering one muscle group, as happens with “leg days,” “arm days,” or “chest days,” and then being in recovery mode for several days.

Another very important limitation I have noticed from “body part splits” is that quite often, the lower body is not trained to the same level as the upper body. This is not ideal for athletic performance or general longevity. In a four- to five-day weekly training split, there might be three or four upper-body focused days, with just one “leg day.”

Additionally, the upper-body workouts are always broken down into specific muscle groups, while the very important lower-body muscles all get dumped under the “leg category.” I may be generalising a little here, but this is quite common and is one of the reasons why bodybuilding or generic gym programs miss out on critical programming elements.

Stimulate a little — rest — repeat. Two or three quality sessions per week, done consistently over time, will lead to huge long-term progress, provided you keep striving to increase the stress of the stimulus.

How to Get the Benefits of Strength and Type IIa Hypertrophy Without Blunting Speed

You can build strength and size without interfering with speed and power if you manage fatigue and plan your training goals across the year.

When the goal is to get bigger and stronger, like in the and , total training volume and, as a result, fatigue are higher. This extra work builds the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the Type II fibers and upgrades your overall force potential. The trade-off is that these phases can create some short-term fatigue and slightly blunt club head speed while you are in the middle of them. That is completely normal and is not cause for concern. It is impossible to be at maximum speeds while simultaneously trying to maximise strength or hypertrophy.

Strength training and activity in general tend to shift some of the fastest Type IIx fibers toward the slightly slower, but more fatigue-resistant, Type IIa fibers. This may sound like a negative issue, but it is likely a beneficial trade off. As the cross-sectional area of these fibers increases, they can produce more force while still contracting fast enough to help with club head speed.

Club head speed is an explosive activity, a blend of strength and speed, rather than a pure maximum speed activity. Bigger Type IIa muscle fibers play an enormous part in explosive strength. I dug into this further in the Science of Speed article .

The same principle applies in other rotational power sports, like track and field throwing and baseball. Baseball pitchers, for example, often throw dramatically faster as they gain muscle and strength. This is one of the key findings that Driveline Baseball, a premier baseball training facility, regularly reports. The added lean mass and force potential simply allow them to produce more power in the same motion. Golf is no different.

Here is a video of Valerie Allman, the world’s best female discus thrower, performing strength training to support her goal of throwing the discus farther. This type of training is close to perfect for golfers. Her potential for club head speed would be very high.

Short-Term Fatigue, Long-Term Gains

When training volume is reduced and you move into the Velocity or In-Season programs, fatigue drops, explosiveness and rate of force development are maximised, and those now bigger and stronger Type IIa fibers can then be expressed as high-speed power houses. This is when club head speed typically peaks, especially if combined with specific swing speed training.

During the in-season program, the goal shifts to maintaining those strength and power levels with lower volume and minimal fatigue so you can perform your best on the course.

Track and field athletes are a great example. Sprinters and jumpers lift heavy year-round but manage fatigue through moderate volumes, staying far from failure in explosive work, and prioritising recovery between high-intensity sessions.

Golfers can follow the same logic. Build the base in the off season with higher volume strength work, then emphasise lighter, faster, lower fatigue training as you move into peak season.

The sequence of Mass → Force → Velocity → In-Season follows a sequential progression, with one program setting up the next. This is one of the things that separates Fit For Golf from other “Golf Fitness” resources. I am not providing “golf workouts”. I’m providing structured, year round programming, with key physiological adaptations in mind.

You get access to all of these programs with the 7 Day FREE trial on the Fit For Golf App.

6. Strength Training vs Exercising With Weights

This is one of the most important distinctions golfers need to understand. A lot of people lift weights, but very few actually strength train. There’s a big difference between strength training and exercising with weights, and that difference largely determines whether your workouts will actually stimulate adaptations or not. It is entirely possible, and quite common, for people to put significant time into their “workouts,” but not stimulate adaptations.

Strength training means you have structure, intent, and a plan to get stronger over time.

Exercising with weights is different. You are using weights and “working out,” but there’s no plan, no map for progression, no measuring, little to no progressive overload, and eventually, no stimulus for adaptation. Both have value, but only one truly develops strength and all the golf performance benefits that come with it.

Strength Training

When you’re strength training, you’re following a program that’s designed to make you stronger, not just sweat or get tired. There’s a clear plan. You know what you’re doing each session, and you’re trying to do a little more over time.

It doesn’t need to be complicated, but it does need to be progressive. You record what weights and reps you do, and you aim to lift a bit heavier or do an extra rep when you can. You stick to a structure long enough for your body to adapt.

That’s the key: your body only adapts if the stimulus changes. If the training load stays the same, the body has no reason to get stronger. Strength training is the process of applying enough stress to force adaptation, then repeating that process consistently.

Stimulus → Adaptation → Improved Capability.

That’s how it works, no matter who you are or what your sport is.

How do you know your strength training is stimulating adaptation? You are gradually able to use heavier weights in your training exercises. Nothing else provides as good feedback as this simple metric. For example, if you compare your five-rep max in key compound exercises year after year and there is no progression, you are not adequately stimulating adaptation.

There should be big increases in the first 3, 6, and 12 months of your strength training “career.” After this, gains will slow dramatically. After two years of consistent, real strength training, further gains will be quite hard. The good news is that by this point, your physical capabilities will be completely transformed, and very small gains or even maintenance over the long term will keep you in a great spot.

Resistance Exercise

Most people who lift weights are doing resistance exercise, not training. They go to the gym, do a few familiar exercises, usually the same ones, at the same weights, for the same reps, week after week, year after year. Then they wonder why “lifting” didn’t increase their club head speed or change their body’s appearance or function.

This type of exercise is still very healthy and beneficial. Any exercise is a huge positive compared to doing nothing. It’s just not enough to keep improving. Once your body gets used to a routine, the adaptations stop. You might maintain the level you are at for a while, but you won’t make long-term progress, and Father Time will be winning the tug-of-war by more than necessary.

That’s why you’ll see two people both “lifting weights,” one making great progress in strength and speed, the other staying exactly the same for years. The first is training. The second is exercising.

Why Tracking and Feedback Matter

If you don’t know what you lifted last time, you can’t know if you’re improving. That’s one of the big advantages of the Fit For Golf App. It logs everything for you. Each session, you enter the weights you used and how many reps you did for each set. The app automatically tracks your estimated one-rep max and shows your progress over time. You also get notified of new personal bests, boosting motivation and satisfaction.

This feedback loop is critical. It lets you see whether you’re actually getting stronger. If you’re not, you know something needs to change, or you’ve reached your strength ceiling, which is highly unlikely.

The truth is, almost nobody in commercial gyms is anywhere near their true strength potential. They just haven’t trained hard enough, consistently enough, or with enough structure to get there.

Equipment and Environment

Being completely honest, the distinctions I have outlined above magnify some of the limitations of home training with limited equipment.

Don’t get me wrong, you can make great progress . About 55% of Fit For Golf App users actually follow . I absolutely do not want to turn anyone off training at home if that is what suits their schedule and preferences.

It is important to understand that it is not the same though. As we get stronger, we require a bigger stimulus to keep progressing. This is a challenge for many muscle groups when you have limited equipment and only light weights, especially in the lower body.

What about adding reps? This works to a point, but revisit the section on above to see where it falls short compared to progressively adding weight.

Every time an app user switches from home training to gym training, they immediately notice the difference.

This won’t be feasible for everyone, but if it’s at all possible, I could not recommend setting up a home training or gym space any more strongly. It is a complete game changer.

(Please don’t send me emails asking what to get for a home gym. There are endless, excellent reviews online, and it is completely dependent on your budget and space.)

The Bottom Line

Strength training has structure, progression, and intent. Resistance exercise is unstructured activity involving weights. Both have value, but only strength training develops the qualities that actually transfer to your golf swing.

If you want to hit it farther, feel better, and keep improving year after year, you need to train, not just exercise. The Fit For Golf App makes this a lot easier.

7. How Heavy Should I Lift?

Finding the Right Starting Weight

This applies to the vast majority of exercises. Choose a weight you are sure you can lift for five reps. Perform five reps, and based on how it feels, add a little more weight, still being confident you can do five reps. Repeat this a couple more times and you will find a weight that is of moderate difficulty for five reps.

A good weight to stop at is one that you lifted for five reps, and if you absolutely had to, you maybe could have lifted for seven or eight. This is about three reps in reserve and a nice intensity level to start with.

If you are a complete beginner, go even easier for the first few sessions. Finishing each set with three or four reps left in the tank is fine. It is better to start too light and progress gradually than to overdo it early and stall or get hurt.

If you are new to training, you will get stronger quickly. The goal from here is to add very small weight increments in each workout until you cannot. In the next sections I will explain this method, and another progression method, in more detail.

Simple Linear Progression

For this example, let’s imagine you have determined that 95 lbs for 5 reps is an appropriate starting weight on the bench press. You successfully complete 3 sets of 5 reps with this weight and feel like there was room for a little more weight.

Perfect. Next session, add a small amount of weight, maybe 5 lbs, so you’re up to 100 lbs. If you can still complete three sets of five, increase again the following session to 105 lbs. These small, steady jumps might not sound like much, but they add up quickly. That’s progressive overload in action.

In simple terms for linear progression:

- Use a weight that allows 3 sets of 5 reps.

- If it feels easy, add a small amount of weight in the next session.

- Keep increasing gradually until 3 sets of 5 reps is right at your limit.

- Whenever possible, add another small increment.

You will reach a point where 5-pound, and even 2.5-pound, jumps from session to session are too big. When exactly this happens will depend on the exercise and your training experience.

Adding 5 lbs to a 200 lb load is a much smaller percentage increase than adding 5 lbs to a 50 lb load, and will be sustainable for much longer. It’s a good idea to think about weight increases in percentages rather than absolute amounts. Increasing a dumbbell lift from 20 lbs to 25 lbs feels much harder than increasing a barbell lift from 200 lbs to 205 lbs. It’s the same 5 lb increase, but a completely different relative increase.

Double Progression Method

You will eventually reach a point where you hit a plateau with the linear progression method outlined above. This is completely normal. Strength increases slow down drastically after the first few months of training. When this happens, the double progression method is an excellent option.

- Start with a weight you can lift for 3 sets of 5.

- Stay with that weight until you can do 3 sets of 8. This may take many sessions.

- Once you can complete 3 sets of 8 reps, increase the weight so that in your next session you are back to 3 sets of 5 reps with a heavier load than before.

- Keep repeating this process.

This method gives you more time to stimulate the adaptations necessary to go up in weight, which becomes increasingly important as progress slows down.

The key with both methods is that there is a clear plan and intent to gradually increase the weight you are using.

Why We Need Progressive Overload

The ability to use more load over time is what proves you are stimulating adaptation.

Gradually adding load over time, is the best proof that you are stimulating strength adaptations.

This ties in with why tracking your training is so important. The Fit For Golf App prescribes crystal clear instructions on exactly what to do in each workout, and makes it simple to record the weight used and reps completed for each set. The progress section allows you to monitor your strength (and club head speed progression) over various time periods.

If the numbers aren’t moving up over time, that’s feedback that something needs to change. Or, you may be at a point where you are just happy to maintain, that’s OK too.

How Strong Is Strong Enough?

Another common question that comes up is: Do I ever reach a point where I should stop trying to get stronger?

For almost all golfers, the answer is no. The vast majority are nowhere near their true strength potential and will benefit from further increases in strength. In general, we need to set higher strength standards for golfers (and non-golfers) who are interested in maximizing performance and longevity.

For most golfers, more strength will almost always be desirable for better speed potential and greater resilience to fatigue and injury. We also need to remember that the higher we can raise our strength peak, the more we have in reserve as we get older. The goal is to raise the peak and slow the decline.

As long as you are increasing strength patiently and progressively, and not “number chasing,” your muscles, tendons, and connective tissues adapt extremely well to the stresses applied. The small risk of an occasional strain or minor injury is massively outweighed by the long-term benefits of being stronger — both for golf performance and overall health.

Research consistently shows that properly performed strength training has a lower injury rate than almost every other sport, including golf itself. Strength-training-related injuries can almost always be traced back to training errors — insufficient warm-ups, too rapid an increase in training loads, trying to squeeze out “one more rep” when technique has broken down, or ignoring early signs that something isn’t feeling right.

There will come a time when progress slows, and you may only make small increases over long periods. Or you may be training hard and simply maintaining. That is completely normal once you are years into your training. By that stage, you will have already transformed your physical capabilities, and maintaining those levels is an enormous advantage for golf performance and long-term health.

Strength Standards for Golfers

A very common question is “what’s a good strength level in ________ exercise”? That’s a difficulty question to answer based on many variables, and every time I try to provide guidelines, someone isn’t happy!

I have tried to provide some benchmarks in the table below, that you can work towards. Note how I said work towards, I am not saying you should feel bad or aren’t doing a good job if you can’t reach them now!

It’s important to note that these standards reflect results from actual strength training (covered later), not simply exercising with weights. There’s a big difference. These numbers assume structured, progressive, very high effort, training designed to make you stronger over time.

How long it takes to reach each level depends on your starting point, training consistency, and how well you apply the fundamentals. As a rough guide:

• Solid: Typically achievable within about 6 months of consistent, progressive training, two to three times per week.

• Strong: Usually reached after 12–24 months of steady, well-structured strength training. You can get here, but you must strive for progressive overload. There must be a good plan in place that you stick with, and you must try hard!

• Very Strong: Reflects roughly 2+ years of dedicated, progressive training with minimal long breaks. This level requires making strength training a big priority in your life, it’s not for everyone. It doesn’t just happen from “showing up and working out”, which is what many, even consistent trainees do.

There’s a wide range in how individuals respond to training. Genetics, age, muscle fiber makeup, recovery ability, and previous experience all play a part. Some people will make rapid progress, others will take longer, but everyone can make significant improvements if they train with purpose and consistency.

Hitting the “Strong” range across most lifts is a great target for golfers who train consistently.

In regards to the relative to bodyweight numbers, If you’re carrying 20, 30, or 50 lbs of extra body fat, these relative strength levels may seem high. They’re well within reach for reasonably lean, well-trained people.

Getting body fat down, and strength levels up is great goal for most people. and will of course make these standards more attainable.

These aren’t rules or requirements — they’re reference points to help you see where your training stands and where you might still have room to improve.

If you fall below the standards, don’t worry. With 1–2 years of well-structured strength training, your strength levels can be completely transformed, at any age.

The table below represents 5RMs — the most weight you can successfully lift for 5 repetitions with good form.

| Exercise | Level | Male | Female | Male 60+ | Female 60+ |

| Squat (to breaking parallel) | Solid | 1.0×BW | 0.8×BW | 0.8×BW | 0.7×BW |

| Strong | 1.5×BW | 1.2×BW | 1.2×BW | 1.0×BW | |

| Very Strong | 1.75×BW | 1.4×BW | 1.3×BW | 1.2×BW | |

| Barbell Split Squat | Solid | 0.8×BW | 0.7×BW | 0.65×BW | 0.6×BW |

| Strong | 1.1×BW | 0.9×BW | 0.85×BW | 0.75×BW | |

| Very Strong | 1.3×BW | 1.05×BW | 0.95×BW | 0.85×BW | |

| Hex Bar Deadlift | Solid | 1.25×BW | 1.0×BW | 1.0×BW | 0.9×BW |

| Strong | 1.75×BW | 1.4×BW | 1.4×BW | 1.2×BW | |

| Very Strong | 2.0×BW | 1.7×BW | 1.6×BW | 1.4×BW | |

| RDL | Solid | 1.1×BW | 0.9×BW | 0.9×BW | 0.8×BW |

| Strong | 1.6×BW | 1.3×BW | 1.2×BW | 1.1×BW | |

| Very Strong | 1.9×BW | 1.5×BW | 1.4×BW | 1.2×BW | |

| Bench Press | Solid | 0.75×BW | 0.5×BW | 0.6×BW | 0.5×BW |

| Strong | 1.0×BW | 0.7×BW | 0.8×BW | 0.65×BW | |

| Very Strong | 1.25×BW | 0.85×BW | 0.9×BW | 0.75×BW | |

| Pull-Up | Solid | 1 rep @ BW | 1 band-assist rep | 1 band-assist rep | 1 band-assist rep |

| Strong | 5 reps @ BW | 2–3 reps @ BW | 1–2 reps @ BW | 1 rep @ BW | |

| Very Strong | 5 reps @ 1.2×BW | 5 reps @ BW | 3 reps @ BW | 2–3 reps @ BW | |

| Single-Arm Row (DB) | Solid | 0.3×BW | 0.22×BW | 0.27×BW | 0.2×BW |

| Strong | 0.4×BW | 0.3×BW | 0.36×BW | 0.27×BW | |

| Very Strong | 0.5×BW | 0.4×BW | 0.45×BW | 0.36×BW |

Key Takeaways for “How Heavy Should I Lift?”

- Heavy is relative. Start light, focus on good technique, and add small amounts of weight over time.

- Track your training. If the numbers aren’t increasing, you’re maintaining, not improving.

- Progressive overload drives every long-term gain in strength.

- You won’t get “too strong.” The goal isn’t to lift the heaviest weights possible — it’s to increase what your body can do so every swing you make has more potential behind it.

Adjustments for Different Times of Season

Off Season

The off season is when you should strive to stimulate adaptations. This is the time to turn the hose on full blast. Train hard enough and often enough to actually create change.

You have more time away from competition and rounds of golf, so fatigue isn’t as big a concern. That means you can handle more total work and recover from it. Focus on increasing strength, and the size of your Type II muscle fibers, and setting up your body for the season ahead.

When golfers go through this phase properly, they see the biggest improvements in strength, body composition, and long-term power potential.

This is also a great time to try and move the needle with swing speed training.

In Season

Once the season starts, priorities shift. Scores come first. Fatigue and soreness from the gym has to stay low so you can play and practice effectively.

The goal here is simple: maintain what you’ve built, and if possible, continue improving slightly. The good news is that maintaining strength is really easy.

Even two short sessions per week, with a few heavy sets, is enough to hold onto almost everything you built in the off season. You don’t need a lot of volume, you just need to keep the stimulus present.

This is a key part of how I help the PGA Tour players I work with. Managing all the different stressors and making sure things are in order. Scores are the priority.

The biggest change to in season training is NOT a reduction in weight, it is a reduction in training volume. This is primarily done by reducing the number of sets per session, and potentially the frequency of sessions. Moving from 3 sessions per week to 2 sessions per week is a viable option.

Done appropriately, in-season strength training keeps the body strong, durable, and better able to handle travel, practice, and tournament golf. It’s also critical for maintaining muscle mass and club head speed all through the season.

Many golfers, even at the professional level, skimp on strength training in season. This results in a steady decline in power levels as the season goes on, and means they are back to square one each off season. Ideally you want to at least maintain in season, so you are climbing to a higher level each off season, not just trying to get back to where you were the previous year.

Adjustments for Different Populations

Seniors

Age is less relevant than level of physical conditioning. You could have two seniors of the same age, one training to a high level for 50 years, and another completely out of shape and just beginning strength training. Completely different scenarios, which is why creating programs solely based on age is nonsensical. I do love working with both cases though!

The two examples above are on either end of the spectrum. There’s a wide middle ground that most (not all) seniors fall into. For this demographic, the Seniors Program on the Fit For Golf App is perfect. This program follows the same philosophy I instill in all of my programs, while taking into account the need for a more gentle starting point.

Most people are far too conservative with their training goals. The research shows clearly that older adults can make huge strength gains when they train properly, and it’s NOT dangerous.

Start lighter, focus on technique and control, then increase gradually. Within a few months, you’ll be able to handle far more than you thought possible, and your body will feel the difference both on and off the course.

Paul Brumley, 77, 8 hcp

Females

There are no major differences in strength training for males and females. Both can follow the exact same program.

In general, there is a strength difference between males and females, mostly because males tend to have more total muscle mass. On average, males have about 40–60% more upper body strength and 25–30% more lower body strength. This is mainly due to greater total lean mass, not differences in muscle quality or how muscles respond to training. Females also tend to carry a higher proportion of their total muscle in the lower body compared to the upper body. This reduced upper body strength is a huge training opportunity. Few things help female golfers more than developing upper body strength. (Miller et al., 1993; Janssen et al., 2000).

Women can expect the same relative increases in muscle size and strength from training as men. When training is matched for effort, volume, and frequency, the percentage improvements are very similar. Men often gain more total mass simply because they start with more muscle, but the relative progress is the same. (Roberts et al., 2020; Grgic et al., 2022).

Females can often perform more reps with the same percentage of 1RM compared to men, and tend to recover faster between sets and sessions. This is partly explained by a slightly higher proportion of slow-twitch fibers and greater fatigue resistance. (Hunter, 2016; Fulco et al., 1999).

None of this changes the overall training guidelines. The same principles apply. Train hard, progressively overload, recover, and repeat.

Finally, to clear up one of the biggest myths, you will not get too muscular. Lifting heavy will not make you “bulky.” Gaining large amounts of muscle requires a significant calorie surplus and years of consistent, high-volume training. Strength training will make you stronger, more athletic, and more resilient. The benefits for bone health, tendon strength, and long-term wellbeing are enormous. (Phillips, 2014).

Susanne, 61, 12 hcp

Juniors

Strength training is absolutely beneficial and safe for juniors of all ages. Traditional strength training is not where I would place a lot of attention for juniors, however. This is a time when maximising speed, coordination, and building competency in as many different movement patterns as possible will be hugely beneficial.

Juniors should sprint, jump, throw, and hit all different kinds of balls as hard as they can. Playing different sports is ideal, but even basic activities at home go a long way. On top of these sports activities, general play like climbing, tumbling, wrestling etc is all fantastic.

Through the teenage years, as puberty kicks in, strength increases come quickly. This is when introducing some more structured strength training makes most sense, but it should not come at the expense of what is listed above.

The main priorities are:

• Keep it fun and avoid burnout.

• Build coordination and speed.

• Encourage a wide range of activities, without forcing them.

In terms of “golf specificity”, the younger, the better for developing a swing that prioritises club head speed. Get them a radar, teach them what club head speed and ball speed are, and make it fun to track progress. They’ll figure out the rest on their own.

What About Sport Specific Training?

Most of what’s called “golf-specific training” is nonsense. It’s usually prescribed by people who don’t understand how physiology underpins performance. They get caught up in movement pattern similarity and ignore, or don’t understand, the need to actually stimulate adaptation.

There’s no such thing as “golf strength.” Strength is a product of the physiology in our muscles and nervous system. These same muscles and nervous system are what produce force in any activity we carry out. Our specific skill and movement mechanics in the sporting task, in our case, the golf swing, is what determines how well our strength is transferred, not whether the exercises we used to develop this strength are “golf specific” or not. When you are trying to swing a club at high speed, you’re relying on the adaptations you stimulated in training, not what the exercise looked like.

The vast majority of high level athletes in rotational sports train almost identically, because the adaptations we’re targeting happen at a basic physiological level. Track and field throwers, baseball hitters and pitchers, hockey players, hurlers – these athletes often display enormous potential for club head speed without ever having practiced golf, never mind performing “golf-specific” exercises in their training. They’re powerful because their neuromuscular systems have been developed to produce force quickly, both through their physical training and sports practice.

Now, is there a middle ground? Of course. Some exercises that resemble the golf swing can be highly effective, and I include them in Fit For Golf Programs. The key is that these exercises must still stimulate adaptation in the nervous system or muscles, otherwise there is no training effect, and you would be better off simply practicing your swing.

Sure, you can develop some swing feels in the gym, but there’s a strong chance you are using time poorly and neither improve your swing nor develop physically.

The vast majority of golfers, even those who’ve exercised with weights for years, still have massive room for progress with basic, structured, progressive strength training. This is what delivers real physiological adaptation — the kind that moves the needle.

So yes, there’s a place for “sport-specific exercises”, but they are a very small piece of a quality strength training program. The biggest transformation for most golfers will come from getting much stronger, while simultaneously working on swing mechanics and speed training.

Swing mechanics and practicing swinging fast are where the golfer develops the ability to transfer their physiological capabilities to their swing.

Get brutally strong → develop great swing mechanics through intense practice → do targeted speed training.

That’s the combination that builds real performance.

8. Safety, Myths, and Flexibility

Strength Training and Injury Risk

A lot of people, especially seniors, worry about hurting themselves with weight training. It’s understandable. Strength training has had a reputation for being risky or hard on the body for decades. The problem is that people tend to focus on the small risks and forget to weigh them against the enormous benefits. They also forget that people get injured doing the most ordinary things: getting out of a chair, gardening, picking up kids, or swinging a golf club. Nobody tells them to stop doing those.

For some reason, there is still a stigma around lifting weights, especially heavy weights. You’ll often hear that it’s bad for your joints, that it causes “wear and tear” (utterly unfounded claim), or that the risk outweighs the reward. The truth is, there’s no good data to support those claims. When strength training is done with an appropriate build-up, controlled technique, and sensible programming, the injury risk is extremely low, even in older adults.

Data on injury rates shows strength training to be one of the safest forms of exercise available.

Competitive strength athletes (bodybuilding, powerlifting, Olympic weightlifting, and strongman): 1–4 injuries per 1,000 training hours (Keogh & Winwood, 2017). These data come from athletes training at high intensities for competition, often pushing physical limits and handling very heavy loads.

Recreational lifters (regular adults training for health and fitness, not competition): 0.31 injuries per 1,000 hours for men, and 0.05 for women (Aasa et al., 2021). Participants trained at least twice per week for six months or more, mostly using standard gym-based resistance training with free weights, machines, and functional equipment.

For context:

Golf practice and play: 1–6 per 1,000 hours (Fradkin et al., 2007).

Running: 2–12 per 1,000 hours (Videbæk et al., 2015).

Pickleball: 3–6 per 1,000 hours (Merriman et al., 2023).

Yoga / Pilates: 2–6 per 1,000 hours (Cramer et al., 2019).

Even at the higher estimates, strength training remains among the safest physical activities you can do.

Heavy Strength Training in Older Adults

Recent research has shown that heavy strength training, meaning loads above 80–85% of one-rep max, is safe and extremely effective for older adults. A 2024 review in Sports Medicine Open (Hernandez et al., 2024) found that heavy and very heavy loading protocols produced large improvements in strength, rate of force development, and function without increased injury risk when performed in supervised, progressive settings. The authors concluded that healthy and clinical older adults “may, and should, train with heavier loads than current guidelines” to maximise performance and health outcomes.

Beyond Safety: The Broader Benefits

The benefits go far beyond safety. A 2022 meta-analysis in the British Journal of Sports Medicine (Kraschnewski et al., 2022) found that people who strength train have a 15–20% lower all-cause mortality risk, including lower rates of cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Strength training also reduces the risk of injuries in other activities. Stronger muscles and tendons protect joints, absorb load more effectively, and reduce the likelihood of overuse injuries. Training through a full range of motion improves tissue capacity and mobility, not wear and tear.

When people do get hurt in the gym, it usually comes down to the same things that cause injuries in any activity: doing too much too soon, using poor technique, or not recovering properly. That’s not a problem with lifting weights, it’s a problem of impatience and poor judgment.

Strength Training and Flexibility

A common myth is that lifting weights makes you tight or reduces your range of motion. It doesn’t. When you lift through a full range of motion with control, flexibility actually improves. The muscles, tendons, and connective tissues adapt to the ranges they are trained through and become stronger and more comfortable there.

This has been shown clearly in research comparing strength training and stretching. When people train through a full range of motion with proper control, flexibility improves just as much as, and often more than, from stretching alone. The reason is simple: you are taking the joint through the same range, but you are also asking the muscles to produce and control force there, which creates a more lasting adaptation (Afonso et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2022).

If someone feels tighter from lifting, it’s not because strength training reduces flexibility. It usually happens from training in short ranges, rushing repetitions, skipping recovery, or doing too much too soon. The solution is not less lifting, but better lifting: full ranges of motion, consistent technique, and appropriate training volume.

For golfers, this is especially important. The swing demands mobility and strength through range. Exercises such as deep squats, split squats, Romanian deadlifts, and controlled cable rotations build usable flexibility — strength and stability at the end of your movement, not just looseness. When you can control force at these end ranges, your body becomes more resilient and your swing more repeatable.

So the truth is the opposite of the myth. Strength training does not make you stiff. It helps you move better, with more control, power, and confidence through every part of your swing.

The Bottom Line

Strength training, even heavy strength training, is not inherently dangerous. When approached gradually and intelligently, it is one of the safest and most beneficial things you can do for your health, performance, and longevity.

Yes, there are small risks involved, as there are with everything. But what we know for certain is that if you don’t strength train, you are setting yourself up for a predictable loss of muscle mass, strength, and power. That loss is a much bigger threat to your health, mobility, and golf performance than the small risks that come with training.

“If you think strength training is dangerous, try being weak.” — Brett Contreras

9. Practical Application: Periodised Training for Golfers – Fit For Golf Programs

This is where we take the science and put it into a structured plan.

I don’t prescribe “golf workouts.” I provide complete, periodised training programs that build the physiological qualities that underpin golf performance. It’s more than “exercises” and “workouts”, it’s a long-term road, proven by tens of thousands of golfers, including multiple PGA Tour winners.

Every Fit For Golf program has detailed structure, logical progression, and a clear emphasis.

There are programs for all levels of fitness, from home and the gym. Beginners to training don’t need much nuance to their training, the key is getting consistent with the program most appropriate for them.

For more serious trainees, with gym access, and 45-60 mins of training time available 3 x week, my favourite progression in the app is the Mass, Force, Velocity Programs.

Each program runs for 12 weeks, with 3 workouts per week, 36 workouts per program. Across the Mass, Force, and Velocity programs, that’s 108 workouts, to become a completely transformed golfer.

This is a level of long-term planning and structure you simply don’t get anywhere else.

Mass Program – Early Off-Season (November to January, 12 Weeks / 36 Workouts)

The primary goal of the Mass Program is to increase the size of the Type II muscle fibers, while improving general conditioning and body composition. It’s the best program on the app for gaining muscle mass and losing fat (the fat loss part still primarily comes down to nutrition and other activity, however).

For long term club head speed development, and truly reaching your potential, increasing the size of your Type II muscle fibers is critical.

The program focuses on accumulating a high volume of moderately heavy lifting. It does this by incorporating a form of “cluster sets” that hits a very nice sweet spot of volume and intensity.

The changes in muscle mass, strength, and body composition from the Mass program have blown users away more than any other program on the app.

This program provides a great base for what comes next, in the Force Program. You’re increasing muscle cross-sectional area, work capacity, and technical consistency. It’s demanding, but it works. Most golfers finish this block stronger, leaner, and fitter than they’ve ever been.

It’s essential to study the program details section of the Mass Program, and complete the Mass Prep program before starting Mass. It’s a demanding program, and you must be adequately prepared.

Force Program – Late Off-Season (January to March, 12 Weeks / 36 Workouts)

After the Mass Program, the next 12 weeks are dedicated to the Force Program. The volume of lifting reduces, but the weight increases.

The goal is to take the bigger (and stronger) muscles you built in Mass and and fully maximise their strength.

It is common for users to lift weights heavier than ever before during this program. If you think back to the explanation of structural and neural adaptations at the start of this article, Mass is primarily focused on structural adaptations. Increased size of the Type II fibers.

Force also works on these same structural changes, but will also have a bigger impact on neural adaptations. Especially in phases 2 and 3 as the reps per set really drop, and the weight approaches maximal levels.

If you complete 12 weeks of Mass and Force and aren’t stronger and more powerful than ever before, I will be happy to send you a refund. I guarantee you will have never made such progress in 6 months of training.

Velocity Program – Early Season (April to June, 12 Weeks / 36 Workouts)

This is a program for those who are particularly interested in maximising their explosive power and club head speed. Benefits will be higher if a high level of muscle mass and strength has already been built. This is why there is a long term methodical plan in place.

When a golfer has a high level of muscle mass and strength, which are developed extremely well by the Mass and Force Programs, they have a very high potential for explosive force. The Velocity Program is a great way to maximise this potential.

There is a big emphasis on moving light weights extremely quickly, while simply maintaining muscle mass and strength. The beauty of this two-fold. Light weights, when lifted very quickly, with sets cut short before any fatigue sets in, are excellent for improving Rate of Force Development, and are also not fatiguing.

Increases in RFD are wonderful for transferring to increased club head speed, and you will also be less fatigued than the periods you were doing Mass and Force meaning better freshness for your Swing Speed Training.

Golfers who complete the Mass → Force → Velocity progression in conjunction with Swing Speed Training often see up to 10mph gains in on-course club head speed, not just in training.

This program is very different to generic weight lifting programs, as the primary goal is supporting speed and power development, not simply muscle mass or strength.

Adrian Tedeschi, 45, 6.2 hcp

In-Season Program – Peak Season (July to September, 12 Weeks / 36 Workouts)

During the main playing season, the focus is golf practice and play. You don’t need to keep pushing for new personal bests, you need to keep what you’ve built.

Two to three short, efficient sessions per week are all it takes to maintain strength, speed, and resilience. A few heavy sets per week provide the stimulation required to maintain the structural and neural adaptations you developed, without adding fatigue that interferes with golf.

This type of programming is exactly what the PGA Tour players I work with follow during their long competitive seasons.

A Year-Round Framework

This full sequence, Mass, Force, Velocity, and In-Season, covers a complete year of development.

4 programs spanning 12 weeks and 36 workouts each.

144 workouts you can keep rotating through year after year, completely transforming who you are as an athlete and golfer.

Not every golfer’s schedule is the same, so these blocks can be adapted to fit different seasons or climates. Many golfers in year round golf seasons follow this four program progression.

If you’re not ready for this level of training don’t worry. There are many shorter and more entry level programs on the app that you can use to build towards this plan, if you wish.

10. Summary

Everything in this article leads to one simple point. Golfers who train with structure and consistency hit the ball farther, stay healthier, and play better golf for longer.

The players who stay strong, fast, and durable into their 50s, 60s, and beyond are the ones who treat strength training as part of their game. They know the swing doesn’t exist on its own. It’s powered by the body you bring to it.

You don’t need fancy “golf workouts.” You need consistent, progressive strength training that develops the physical qualities that matter most for golf.

That’s what the Fit For Golf App is built for. Real programs, proven results, and a clear plan to help you get stronger, faster, and more resilient.

Start today. Pick a program, follow it closely, and see what happens.

Start your 7-day free trial

References

Aasa U, Barnekow-Bergkvist M, Angquist KA. Injury risk factors associated with weight training. J Strength Cond Res. 2021.

Afonso J, et al. Strength training vs stretching for range of motion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2021.

Cramer H, et al. Injuries in yoga: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2019.

Fradkin AJ, et al. Injuries in golf: a systematic review. J Sports Sci Med. 2007.

Grgic J, et al. Effects of resistance training on muscle growth and strength in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2022.

Fulco CS, et al. Gender differences in muscle fatigue and recovery. J Appl Physiol. 1999.

Hernandez J, et al. Heavy strength training in older adults: implications for health, disease, and physical performance. Sports Med Open. 2024.

Hunter SK. Sex differences in human fatigability: mechanisms and insight to physiological responses. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2016.

Janssen I, et al. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 years. J Appl Physiol. 2000.

Keogh JW, Winwood PW. Epidemiology of injuries in powerlifting and weightlifting: a systematic review. J Strength Cond Res. 2017.

Kraschnewski JL, et al. Resistance training and mortality risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2022.

Merriman JA, et al. Pickleball injuries: a systematic review and analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023.

Miller AE, et al. Gender differences in strength and muscle characteristics. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1993.

Phillips SM. A brief review of critical processes in exercise-induced muscular hypertrophy. Sports Med. 2014.

Roberts BM, et al. Similar hypertrophy and strength gains in men and women after resistance training when adjusting for effort. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020.

Thomas E, et al. Effects of strength training on flexibility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2022.

Videbæk S, et al. Running-related injuries in recreational runners: a systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015.