As golfers become more aware of the benefits of fitness, resistance training has rightfully taken center stage. But there’s one vital element still missing from many training programs: power training.

The Aging Effect on Muscle

Starting around age 30, we begin to lose muscle mass, strength, and power. This decline becomes more pronounced after age 60. The best countermeasure? Challenging, consistent resistance training — often referred to as weight training or lifting (1).

While strength training is excellent for preserving or building muscle mass and strength, it doesn’t fully address another key physical quality: muscle power.

Power vs. Strength: What’s the Difference?

Muscle strength is about how much force your muscles can generate, regardless of how fast you do it. Think of a heavy bench press or leg press that takes a few seconds to complete.

Muscle power, on the other hand, includes an explosive component. It’s about producing high force quickly — crucial in sports and everyday movements. For example, a vertical jump or a golf swing with high club head speed requires not just strength, but also speed (2).

Power = Strength x Speed

Why Golfers Should Care About Power

In golf, power directly influences swing speed and shot distance throughout the bag. Beyond the course, training for power helps you move better, stay agile, and age more athletically. It even helps prevent falls (3).

Unfortunately, muscle power tends to decline faster than strength or mass as we age. This happens partly due to biological changes, but also because power is rarely trained in adults who are no longer competing in sports (4).

A 2024 review confirmed that muscle power deteriorates at a faster rate than strength due to a combination of reduced neural activation and decreased Type II fiber capacity (2).

The Physiology of Power Loss With Age

Our ability to produce force quickly is governed by both our nervous system and muscular system. They always work in tandem, but they adapt to aging and training choices in different ways.

When we try to move explosively, our brain must send rapid signals through our spinal cord to activate the fast-twitch fibers in the relevant muscles. This is the central nervous system at work. The speed at which these signals are sent is known as motor unit discharge rate. A decline in this signaling speed plays a major role in the early loss of explosive capability — more so than changes in the muscle tissue itself (5).

This quality is best trained with high-effort, high-speed movements. Slow and controlled resistance training, or general activity, will not maintain it.

As aging continues, structural changes in muscle become more influential. We lose fast-twitch fibers, and the ones we retain tend to shrink and weaken. Traditional resistance training is excellent for preserving the size and strength of these fibers. For maximum carryover to explosive power, it’s critical to perform lifting movements with explosive intent during the upward (concentric) phase of each rep.

Research shows that early-phase power loss is largely due to neural decline, such as reduced motor unit discharge rates, while structural muscle changes contribute more significantly with advancing age (6)(7).

We want to perform resistance training for the size and strength of our fast twitch fibers, and perform high speed movements for maintaining how well we can recruit them.

It’s not a perfect analogy, but think of your muscles as the car, and your nervous system as the driver. We need to train both!

Aging Athletically

“Aging athletically” means maintaining as much athleticism and movement skill as possible throughout life. You won’t move like you’re 25 forever, but smart, well-rounded training can minimize the decline.

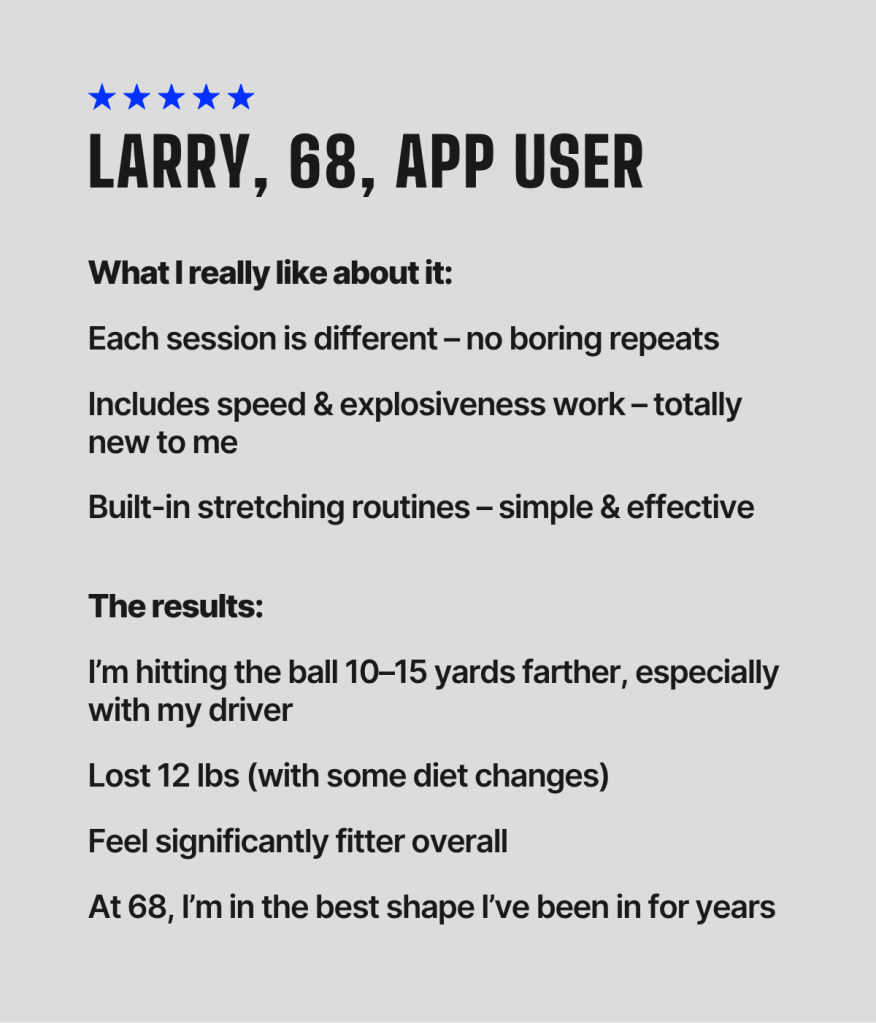

Implementing power training into your routine can support your golf game and daily life. Whether you want to add yards to your drive, enjoy active travel, or play tag with your grandkids, power training is worth the investment.

What Does Power Training Look Like?

You don’t need hours in the gym. Just 5–10 minutes, two to three times a week can make a huge difference. Here are examples of effective exercises:

- Short sprints (flat ground or uphill for lower injury risk) – make sure to read my blog about sprinting before incorporating these

- Bike sprints — stationary bikes work great if you cannot do regular sprints. Think 5-second bursts, followed by 60 seconds of recovery.

- Jumping exercises — can be modified based on ability or injury history, like jumping on a box, performing high-speed squats, or explosive kettlebell swings.

- Medicine ball throws and slams — great for upper-body and trunk explosiveness.

- Swing speed training tools like The Stack System (or speed training with driver).

The key? Express force as quickly as possible. Choose movements where you can move with maximum explosiveness and full intent, and that feel safe for you.

How to Incorporate It

In my own workouts, I perform power exercises right after the warm-up. It primes the nervous system for the upcoming strength session and boosts overall performance. For example, doing a few sets of vertical jumps before squats or ballistic push-ups before bench pressing is a great way to work on power, and get the nervous system and body ready for the upcoming lifts.

You must be well warmed up — never attempt explosive exercises cold.

That’s why the programs in the Fit For Golf App follow a structure of:

Dynamic Warm-Up → Power → Strength

Start Today

🎯 Ready to take your golf fitness to the next level with workouts designed around everything discussed above?

Training for power isn’t just for athletes. It’s for anyone who wants to move well, stay strong, and live life on their own terms — especially golfers.

References:

- Mitchell WK et al. Sarcopenia, dynapenia and the impact of advancing age on human skeletal muscle size and strength. Biogerontology. 2012;13(3):321–331.

- Zemková E, Hamar D. Age-related changes in neuromuscular functions and balance performance: implications for power training in older adults. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2024;21(1):1–13.

- Bean JF et al. A comparison of leg power and leg strength within functionally limited older people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(1):62–67.

- Reid KF, Fielding RA. Skeletal muscle power: a critical determinant of physical functioning in older adults. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2012;40(1):4–12.

- Klass M, Baudry S, Duchateau J. Age-related decline in rate of torque development is accompanied by lower maximal motor unit discharge frequency during fast contractions. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(3):739–746.

- Maffiuletti NA, Aagaard P, Blazevich AJ, et al. Rate of force development: physiological and methodological considerations. Sports Med. 2016;46(4):529–543.

- Power GA, Dalton BH, Rice CL. Human neuromuscular structure and function in old age: A brief review. J Sport Health Sci. 2013;2(4):215–226.